China’s electric vehicle sales surged five-fold in the first 10 months of 2014, powered by Beijing subsidies. In a long-awaited take-off, even unlikely firms like a metals trader and a soda ash producer are pouring money into green transportation.

As China’s demand for luxury and premium cars cools, the Guangzhou autoshow this week hosts a separate event dedicated to green vehicles. But the gold rush is fuelling concern in the industry it may add to overcapacity, leaving new entrants struggling to survive even with state support.

“China’s green vehicle market will be huge,” said Arnold Chan, Deputy Chairman of China Dynamics Holdings Ltd.

The company, more than 11 percent-owned by Chan according to Thomson Reuters data, quit metals trading to start making environmentally friendly electric buses this year after losing money ever since its 2006 Hong Kong listing.

“There are 2 million buses on Chinese roads. A 10 percent share of that market would be enormous,” said Chan, whose new entrant firm is worth about $440 million by market value. It’s unclear how many electric vehicles could in practice replace buses now in service, but as the world’s biggest auto market, China is a magnet for new firms.

Shanghai-listed Tangshan Sanyou Chemicals Industries Co ltd , a Chinese producer of soda ash worth $1.9 billion by market capitalisation, entered the green vehicle business in March. At Shenzhen-listed auto parts maker Wanxiang Qianchao Co Ltd, shares have doubled since parent Wanxiang Group acquired bankrupt U.S. electric car maker Fisker Automotive in February.

The concern over potential over-investment stems from orders for electric buses and cars coming from local governments, rather than individual consumers.

Despite a flood of electric car models coming to the market this year, from BMW and Mercedes Benz to Nissan and BYD, many in China are just not yet ready to buy them, according to a survey earlier this year by consultancy A.T. Kearney.

Some 54 percent of survey participants said incentives wouldn’t be enough to override other concerns. Fully 60 percent of consumers said they expect a minimum driving range of 250 kilometres, much further than the range of most electric cars currently on the market.

CHASING SUBSIDIES

Beijing has introduced a slew of measures over the course of this year to support electric vehicle sales in a move to combat China’s growing pollution problem.

These incentives include renewed subsidies for car buyers, exemption from purchase taxes and public funding to build charging stations. Another key strand that caught the eye of wannabe green vehicle makers was a purchase quota of at least 30 percent by 2016 for the fleets of central government, as well as local government in 88 new energy vehicle pilot cities.

But China’s industrial policies have backfired in the past.

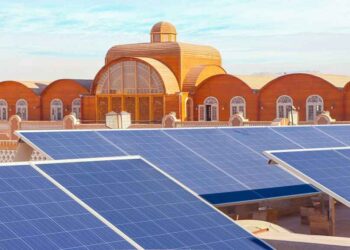

In 2009, Beijing offered hefty subsidies to the solar power industry, triggering a race to develop multi-billion dollar solar projects. But the boom ended badly with the collapse of solar superstars such as Suntech Power Holdings and LDK Solar Co Ltd.

In shipbuilding, meanwhile, government-backed expansion also led to a bust that brought hundreds of small to mid-sized shipyards to the verge of bankruptcy.

“If the government keeps subsidizing an industry which itself is not profitable, there will be a lot of trouble,” UBS Hong Kong-based auto analyst Hou Yankun said.

The potential for a supply-demand mismatch worries even new-comers like China Dynamics.

“I see a lot of people rushing into this business,” Deputy Chairman Chan said. “Many will be weeded out in the future. Only those with real competitiveness can survive.”